Now that we’ve all mastered the art of identifying Empidonax flycatchers thanks to a certain field guide published a year ago, it’s time to start working on Kingbirds and Myiarchus flycatchers! I jest a bit, of course, birders will never stop puzzling over Empids. But Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Empidonax and Pewees certainly gave us a framework for identification that upped our level of discourse and analysis. The next volume in this three-book series is now out: Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Kingbirds and Myiarchus by Cin-Ty Lee, illustrated by Andrew Birch, and it is as informative and well-organized and lovely to look at as the Empid/Pewee volume.

Sixteen species that have been recorded in the United States are covered: six Myiarchus flycatchers and ten Kingbird (Tyrannus) flycatchers. There is also a section on Hybrids. It’s an intriguing mix of commonly seen species like Great Crested Flycatcher and Western Kingbird; species with geographic niches like Brown-crested Flycatcher and Thick-billed Kingbird; and genuine rarities, like Loggerhead Kingbird. As with the first volume, I was surprised to see the inclusion of a species that has only been seen in the U.S. a handful of times, only to realize how important it is to have a resource that will help birders differentiate amongst these very similar looking birds.

Introductory Material

Sixteen species, 190 pages. The guide could be described as sixteen species accounts wrapped up in introductory text. In addition to the general introduction to the book’s material, there are introductions to each genus: Myiarchus and Kingbirds (Tyrannus). These are essential reading, maybe even more important than the Species Accounts. Because, although these flycatcher groups don’t have the sexy, challenging reputation of Empidonax flycatchers, they can be confusing–ask any East coast birder trying to figure out if a vagrant bird with worn tail feathers is a Western Kingbird or a Cassin’s Kingbird. Or a birder trying to figure out if a medium-sized Myiarchus in Arizona is a Nuttings’s, Ash-throated, or Dusky-capped Flycatcher. Lee and Birch strongly believe that even look-alike flycatcher species can be identified using a holistic approach. This means observing and noting “a combination of plumage and structural field marks, vocalizations, behavior, habitat preference, and seasonal timing” (p. 11). The three introductions present a textbook on how to do that.

The introductions talk first about how to know if the flycatcher you are looking at is a Myiarchus or Kingbird, and then what field marks to concentrate on–whether to look at shape or color or pattern or size, and how to determine the all-important primary projection. They discuss the effects of age and molt on feathers (that Kingbird question above); what types of behavior to observe (differences in where they perch, territorial behavior, flocking); how to listen to vocalizations and read spectograms; how to observe and determine habitat; and how to read and use distribution maps.

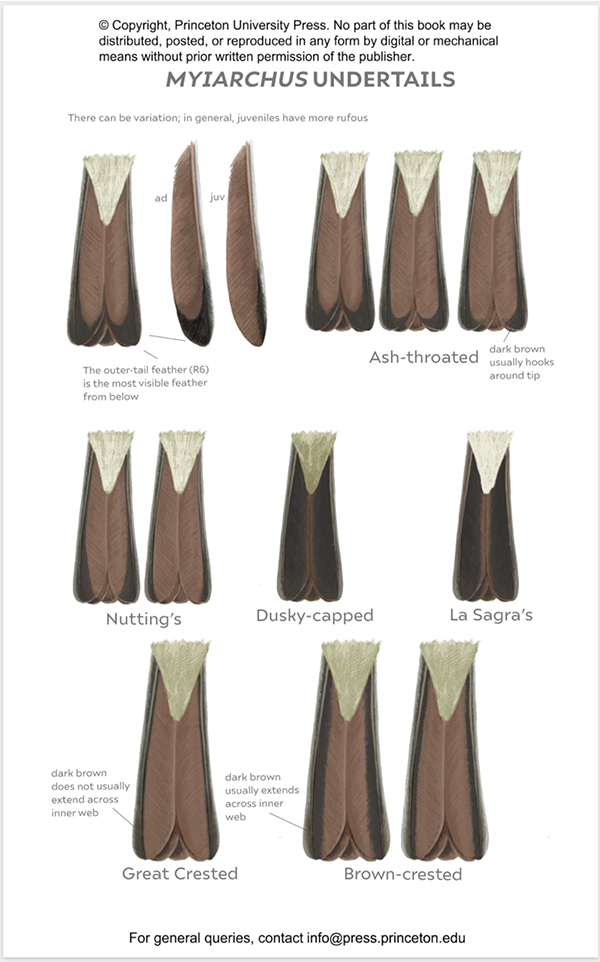

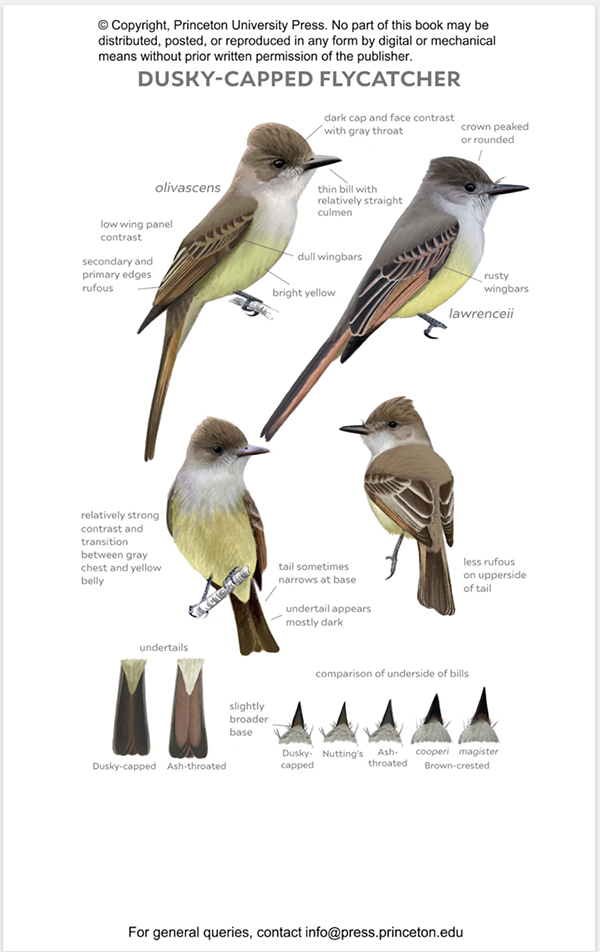

If you read the first book, you may think you know all this already and can skip the material. That would be a mistake, these are totally different flycatcher groups with almost totally different features to learn. Gone are the plates on eye-ring shape, and lower mandible color, in are plates on undertail pattern (a feature I knew was important for warbler identification but had no idea was also significant for Myiarchus identification), still important are plates on primary projection and wing panel contrast. The Habitat section has been greatly increased from the first volume, from a half-page of text and two paintings to two pages of text and twelve clear, lovely, helpfully captioned photographs. It’s one of several changes made by the authors in response to readers’ and reviewers’ comments, and I find it interesting that there is a demand for more information about birds’ environments.*

I particularly like the comparative plates in the genus introductions. Birch’s brilliantly precise illustrations of each species are laid out in comparative plates, with Lee’s text describing the often subtle differences amongst them. For Myiarchus, we can study comparative bill size and shape, crown shapes, body coloration, chest contrast, face contrast, and, of course, undertail pattern and color. Two side-by-side plates portray the significant identifying features of the four most commonly occurring Myiarchus flycatchers in the United States and Canada–Brown-crested, Great Crested, Ash-throated and Dusky-capped–in a design that masterfully combines whole body images with close-ups of bills and tail feathers and undersides of bills and wings, all with precise explanatory notes. It’s a masterful example of how scientific illustration can inform and be enjoyable to look at, and I’d love to have these plates in mini card form to carry around with me when I visit California.

The Kingbird introductory chapter is shorter, partly because there are less significant features to study, partly because the comparative plates are inserted throughout the Species Accounts sections. There are two parts to Kingbirds, a section on “yellow-bellied Kingbirds” and a section on “white-bellied Kingbirds.” Organizationally that makes sense. And I think it also would make sense to place the two plates comparing four yellow-bellied Kingbirds–Couch’s, Tropical, Western, Cassin’s–at the beginning of that section, and the plates comparing Tropical and Couch’s Kingbird and Western and Cassin’s Kingbirds after their respective species accounts (poor Thick-billed Kingbird stands alone). I do wish there was a note somewhere indicating where they can be found, maybe in the table of contents or a separate listing of comparative plates or even the Index. People seldom use field guides in a sequential manner, they look for the information they want and then move on. So, if you didn’t know these comparative plates existed, you might miss them altogether. I do like the nifty table of vocalizations in the Kingbird introduction, which shows which species give high pitched buzzes, brrrs, chEEs, squeaky notes, twitters, and pips. It’s an effective way to communicate the confusing diversity of vocalizations amongst these species.

Species Accounts

Species accounts vary in length from five to eight pages, and the length surprisingly is not related to the commonality of the species. Fork-tailed Flycatcher is a seven-page bird, partly because the account includes a vagrancy chart (another new feature). Each account begins with traditional information: common name, scientific name, and measurements. A General Identification section gives a thumbnail description of the species, including when it resides in North America, general geographic area, habitats, significant behaviors, a description of its physical appearance (which may be quite detailed), and information on subspecies in North America. The Vocalizations section describes the species’ diagnostic and less diagnostic calls, twitters, chatters, and songs using transliteration and comparisons, also describing the pace and acoustic quality of the sounds. (In the Introduction, birders are directed to the Macauley Library of Sounds from Cornell University and the Xeno-canto website for actual recordings and are cautioned against excess use of playback.) The Habitat, Distribution, and Seasonal Status section gives essential information on habitat preferences, nest description (for species that breed in North America), breeding range, migration patterns and when migration takes place, tendency for vagrancy and where vagrancy usually occurs. The Similar Species section goes into detail about how to differentiate the species from similar looking species, discussing differences in structure, plumage, and all the features described in the introductory material (which is why it’s so important to read it!). The depth of detail can be impressive: “The lining of Nutting’s mouth is orange instead of the flesh-color or yellow of Ash-throated” (p. 79). (There are also very detailed directions on differentiating Nutting’s tail hooks from Ash-throated tail hooks complicated by the lack of tail hooks on juvenile Ash-throateds, but frankly I didn’t want to do that much typing.)

Complementing the text are spectograms of distinctive vocalizations, distribution/seasonality map and graphs, and the page every birder will look for first, the plate of illustrations of the species. The spectrograms are much easier to read in this volume, larger and darker. The range maps contain an amazing amount of information: breeding, non-breeding, and year-round range in North, Central, and South America; migration routes for most species (including subspecies migration routes), and vagrancy range. Like the vagrancy table cited above, this is a new, valuable addition to the series, especially to Eastern birders like me who may encounter most of the species in this guide as vagrants. The season abundance charts and vagrancy charts, presented as bar graphs, give a visualization for when birders can expect to see each species; many species have multiple seasonal charts depicting different geographic areas–eleven for Great Crested Flycatcher! I do wish that the key for reading the maps’ colors and lines was on the inside front or back cover rather than page 43. It’s a relatively simple key, six colors and three types of lines, but I have a porous memory and I ended up tabbing the page.

The Species Accounts plates are educational and beautiful. Birch has a deft, graceful way with lines and shapes, so each image conveys the romance of the bird as well as identification features. I am particularly impressed by his way with color. These flycatchers are not the most visual striking species in the avian world (with the possible exception of the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher), but they do have their own subtle beauty in their shades of brown, gray, black and yellow and Birch conveys that very well. Species are depicted in side profile, three-quarter profile, sometimes face-front, sometimes in flight. There are close-ups of important features: for Myiarchus, undertails and undersides of bills and for some tertial feathers and, yes, mouth lining; for Kingbirds, sketches of primary projection and wings in flight. The explanatory captions are in smaller fonts than in the first volume, but still very legible.

As mentioned above, there is a chapter on Hybrids. I was surprised, I didn’t know this was possible, and the authors write that it is indeed a rare occurrence (though I did find an article about a hybridization zone of Western Kingbirds and Scissor-tailed Flycatchers). The text discusses the types of hybrids that have been reported and a chart shows the combinations visually, color coded for most likely, very rare, and highly unlikely (most of the squares). The plate shows the three most reported hybrids: Western x Eastern Kingbird, Tropical x Gray Kingbird, Western Kingbird x Scissor-tailed Flycatcher. I don’t know how often this chapter will be used, but I admire its inclusion in the spirit of complete-ism.

Organization and Back-of-the Book

Like Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Empidonax and Pewees, Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Kingbirds and Myiarchus is well-organized and designed. There is a luxury in devoting a whole book to two genera, there’s room for blank space if a map or text doesn’t fill the whole page, readable fonts, and full-page separations of sections. These page dividers include paintings by Birch, another new feature of this volume. More impressionistic than his scientific illustrations, the paintings are an appealing addition, something we don’t ordinarily find in a field guide and most welcome.

Users may use the Table of Contents or the Index to locate introductory chapters and Species Accounts. The Table of Contents list Species Accounts by text and bird image, a format that will be helpful to birders who are not sure of the name of the bird they’ve seen and want to identify. The Index helpfully lists identification features like “color” and “primaries” as well as bird names (common names only). The three-page Bibliography lists books and articles on bird identification and distribution status, including chapters from Birds of the World, all in impeccable citation style. It is missing one item, the chapter on “Yellow-bellied Kingbirds” in Better Birding: Tips, Tools & Concepts fort the Field by George L. Armistead and Brian L. Sullivan (PUP, 2016), a twelve-page article with comparative photographs.

The list of Useful Websites is still short but has one noteworthy addition–Surfbirds. This website, one of the oldest birding presences on the Internet, is now the archive for “updates to all volumes of the current Field Guide to Flycatchers of North America.” A fantastic idea! Surfbirds.com may not be the most sophisticated website on the Internet, but it is free and presumably will continue to offer its mix of trip reports and identification articles (including some of Lee and Birch’s previous articles).

Authors

Authors Cin-Ty Lee and Andrew Birch are birders and birding writers and artists with day jobs, which makes the publication of their two (and the forthcoming third) books on North American flycatchers an astounding achievement. Cin-Ty Lee is Harry Carothers Wiess Professor of Geology, Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Rice University, Houston, where he “investigates how our planet has evolved with time, from the deepest parts of the Earth’s mantle to the continental crust and to the atmosphere” as well as birding on campus and writing cool birding notes that he sometimes shows on the social media site formerly known as Twitter. Andrew Birch is well-known in the Los Angeles birding community (I had the pleasure of meeting him several years ago at Silver Lake Reservoir, where he showed me where to look for the long-staying Lucy’s Warbler), where he is one of the leaders of the Los Angeles Birders group. He is a co-illustrator of Field Guide to the Birds of the Middle East (1996) and has illustrated many other magazines and articles. Lee and Birch have co-authored field identification articles on birds that are not flycatchers, including dowitchers, loons, pipits, and orioles, for Birding and Texas Birds Annual.

Conclusion

Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Kingbirds and Myiarchus by Cin-Ty Lee and Andrew Birch is an exceptional identification guide, innovative in its focus on holistic identification presented through detailed, readable text; scientific illustrations; diagrammatic presentations of vocalizations and geographic distribution, and explanations of how to put it all together to come up with an identification. The authors have improved on the first volume in this series, Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Empidonax and Pewees, in a number of ways, including expanding information on habitat and vagrancy, improving the readability of the spectograms, and creating summary comparison plates. Most of the birds in this volume are found in the west, but I think Eastern birders will find it useful too. Maybe more useful since Kingbird vagrants often presents knotty identification questions and we Eastern birders often don’t even know where to start, what features to look at other than outer tail feathers. Slim, portable and attractively priced, they can be used in the field or next to your computer as you examine photos, they are also fun to browse through.

These two books are the only identification field guides that focus exclusively on flycatchers. There will be a third book in the series. Cin-Ty Lee tells me that they don’t have a name yet, but the book will be more technical, have a large format, and will include all the plates of the first two volume as well as photos. It will cover all the species of the first two books plus Phoebes, Kiskadees, Elaenias, our one Tyrannulet and any other North American flycatchers out there. It’s something to look forward to. Meanwhile, we have these two volumes. I saw an Eastern Kingbird today in a local park, easily identifiable by its patterned black, gray, and white body and short flights at the tippy tops of the trees. Soon the Empids will arrive–Least, Willow, Acadian, sometimes Alder and Yellow-bellied Flycatchers. And the Eastern Wood-pewees. I need to reread the guide to Empidonax and Pewees, brush up on my Empid identification. And then in September I’ll reread book two’s section on yellow-bellied Kingbirds and Myiarchus flycatchers before my trip to California. I want to be prepared, I want to know my Western from my Tropical from my Cassin’s from my Couch’s, my Ash-throated from my Dusky-capped. There is no magic wand for flycatcher identification, but it’s good to know that there is a well-thought out, beautifully illustrated methodology.

*Cin-Ty Lee kindly answered my questions about the third volume and changes from the first volume at the last minute. Thank you!

** https://www.cintylee.org/about

Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Kingbirds and Myiarchus

by Cin-Ty Lee; illustrated by Andrew Birch

Princeton Univ. Press, April 2024 (U.K. June 2024)

flexibound, 200pp. size: 5 x 8 in., illus: 56 color + 18 b/w illus. 17 maps. 51

ISBN: 9780691240640

$19.95/£16.99

Source link